Toward the middle of the 1st millennium BC, a series of changes in Menorca’s autochthonous culture arose, resulting from the growing hierarchisation of the Talayotic culture and the influence that the colonial powers, who were fighting at the time for control of the Western Mediterranean, would gradually exert over the indigenous culture.

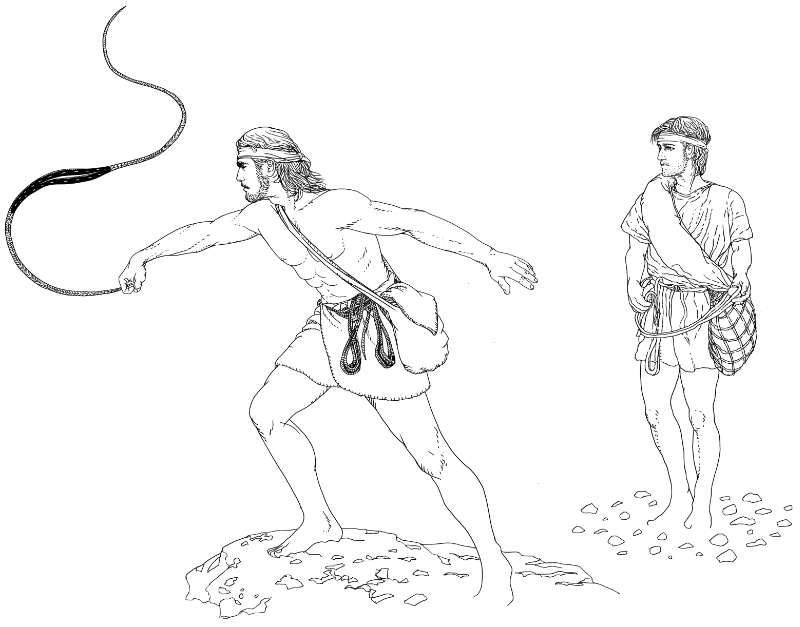

Talayots ceased to be constructed during this period, although they survived within the settlements perhaps as symbolic elements of their past or as territorial landmarks. Meanwhile, a previously inexistent type of structure made its first appearance; the taula enclosure, a type of sanctuary where the community would perform ceremonies of a ritualistic and festive nature. This period is also characterised by the introduction of iron metallurgy, and still more so by the construction of walls around a number of settlements, coinciding with the large-scale arrival of imported materials, especially amphorae used for wine and domestic crockery originating from the Punic colony of Ibiza.

There are no clear signs in Menorca of Punic colonisation in the strict sense of the word, although the intensification of a market for commercial trade has been demonstrated. The archaeological materials discovered through excavations and evidence of the survival of construction techniques from previous periods indicate that earlier ideological structures were conserved during this period.

The world of the living

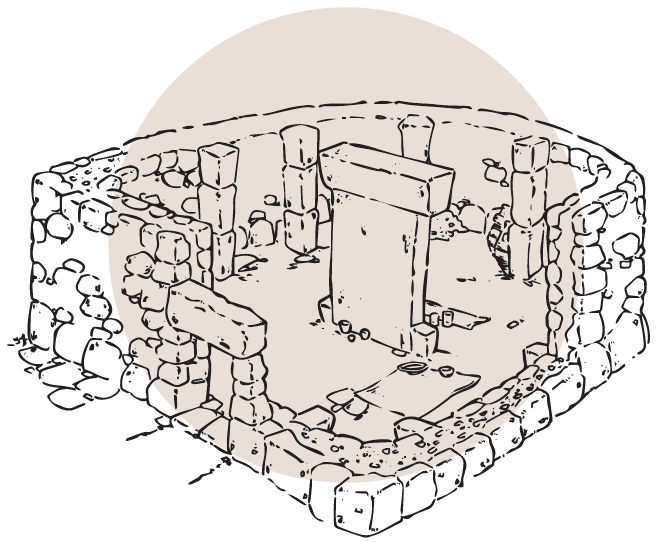

The circles found in the settlements correspond to the last centuries of Menorcan prehistoric culture. Little is known at present about these structures, which were subjected to alterations and changes in usage and distribution of their interiors until as late as Roman and Andalusian times.

Broadly speaking, circles are dwellings that are interconnected without prior planning. They are circular in shape (hence their name) and have double-sided walls with a single entrance, a central open-air courtyard and various surrounding domestic spaces that included perishable roof materials. Seen in association with circles are, first, hypostyle halls, with stone slab roofs supported by columns of the same material, used for storage, and second, a large courtyard at the entrance used to house livestock. Discovered in circles are those elements necessary for the execution of the everyday activities of a family unit, including rest, food production, ceramic and fabric production or the processing of leather or wool.

The families that inhabited the circles laboured in the rearing of goats for milk production, of sheep to obtain meat, milk and wool, and cows and oxen, for their milk and as beasts of burden. They also possessed pigs and horses. To a similar extent, they carried out agricultural activities, and to a far lesser degree, as was the case in previous periods, fishing and gathering were merely residual or secondary practices.

The second typical construction of this period is the taula enclosure, whose central element is the taula itself; a vertical pillar situated at the heart of the enclosure upon which another large stone was placed horizontally, forming what appears to be an enormous T. The multiple archaeological excavations carried out on this type of structure share the discovery of an area of ashes and an accumulation of remains from lambs and kids beside the taula and concentration of broken amphorae scattered in the immediate area, in addition to fragments of Talayotic and Punic ceramic vessels associated with the consumption of these very animals. It is believed that taula enclosures were the site of communal ceremonies and rituals that most certainly involved the consumption of wine and meat.

The world of the dead

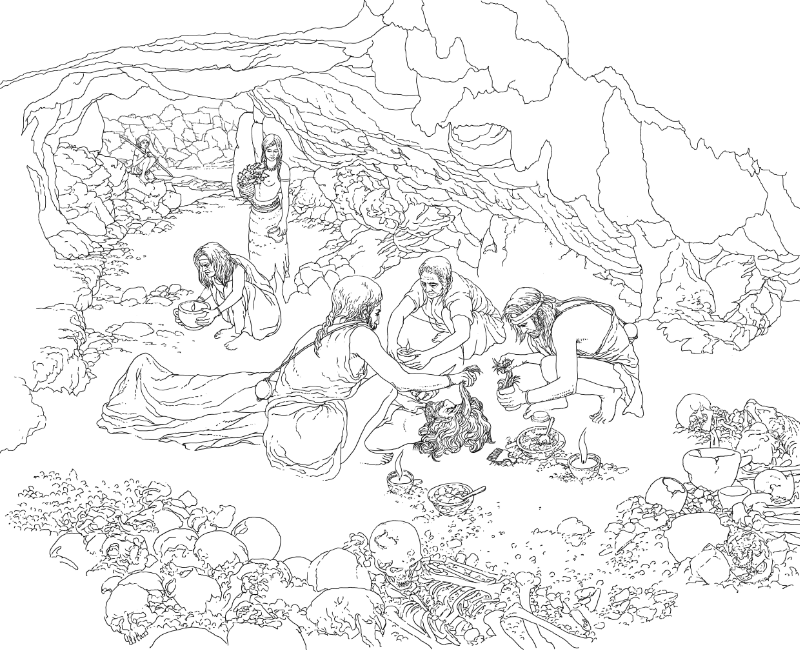

Burial navetas were already part of the past and it is at this moment when, despite the continued use of natural caves as burial sites, the large necropolises of artificial caves or hypogea began to take shape both near the coast and inland. In this final period of Menorcan prehistory, large compartmentalised caves with functional details that differed from those of the previous period became widespread.

The hypogea were collective tombs where a variety of funerary rites were performed. Some rituals involved corpses being placed upon stretchers or in wooden coffins along with their grave goods, while others involved lime burials. In both cases, the presence of bronze in the grave goods diminished in favour of those of iron. Distinctions were not made for the corpses of different individuals. In fact, they were buried together, without separation based on gender or age, although it has been observed that certain individuals possessed more extravagant grave goods than the rest.

Quicklime burials were a novelty in this period. The lime was poured over the body and its grave goods to accelerate decomposition of soft tissue and sanitise the tomb. In some cases, it appears that cremation was done through the prior placement of calcareous stone or lime dust over the body. This allowed fire to consume the soft tissue while the stone turned into quicklime (calcium oxide), and when solidified, the remains were placed inside the funerary site. The reason for preferring one ritual or the other is unknown, although it appears that the different traditions established by each family clan could make for a plausible explanation.